You can follow me on medium: Fareed Khan

Building a production-ready RAG system involves a series of thoughtful and iterative steps.

- It all starts with cleaning and preparing thse data, followed by testing different chunking strategies both logical and traditional to find what works best for your use case.

- Next comes anonymization, which helps reduce hallucinations by stripping away sensitive or irrelevant details.

- To further improve retriever performance, creating subgraphs can help focus retrieval on the most relevant information while filtering out noise.

- On top of the retrieval layer, we introduce a planning and execution system powered by LLMs. This acts like an agent that learns from previous steps, decides what to do next.

- Finally, once the RAG system generates responses, we evaluate its performance using a range of metrics.

In this blog, we will walk through how to build this full-stack RAG system

Using LangChain, LangGraph, and RAGAS (Evaluation), simulating real-world challenges and showcasing practical solutions that developers face while building RAG bots.

This is created on top of the version of nirDiamant guide. Thanks to him for the foundational work.

- Understanding our RAG Pipeline

- Setting up the Environment

- Breaking our Data (Traditional / Logical) Forms

- Cleaning Our Data

- Restructuring the Data

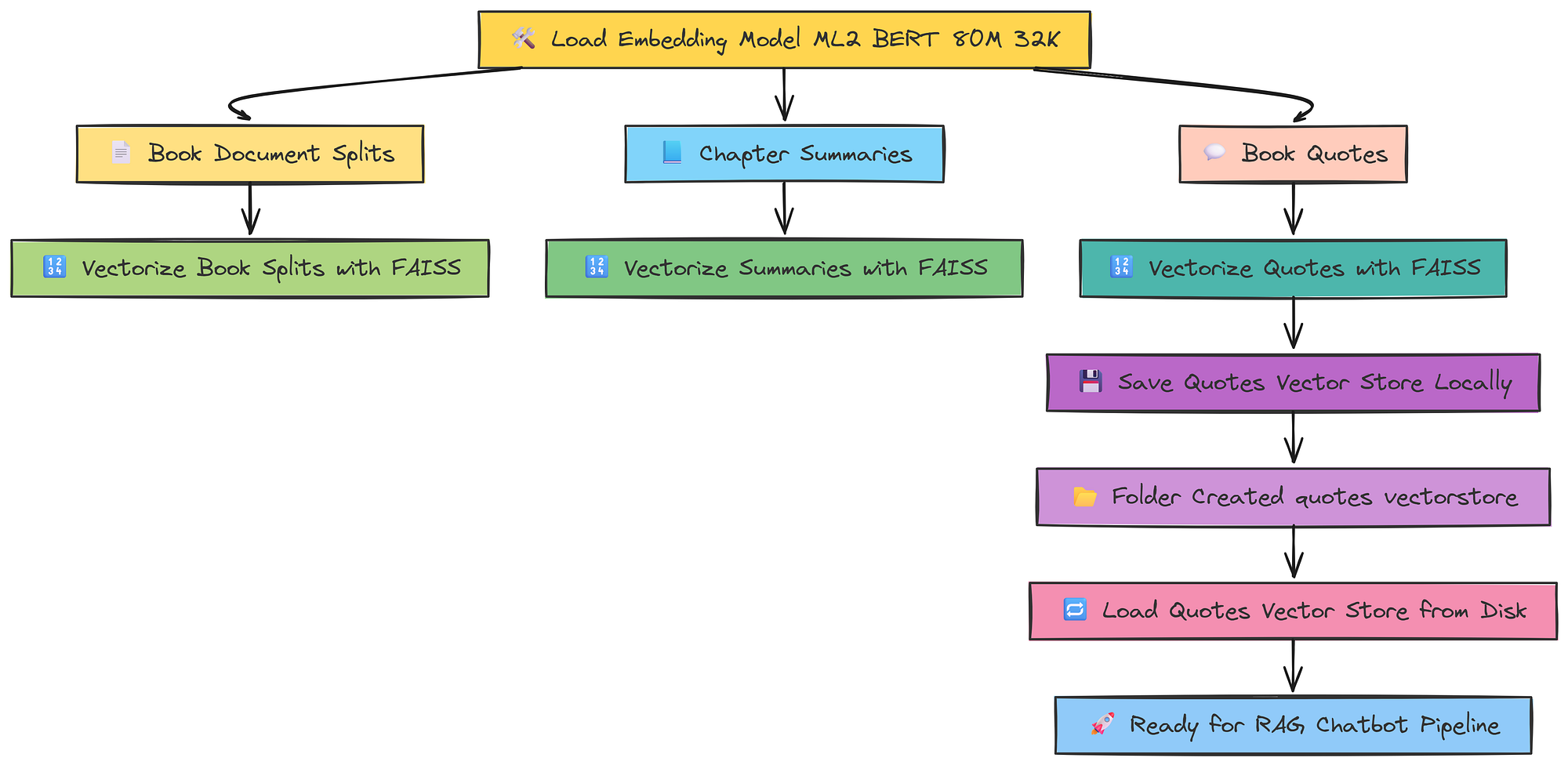

- Vectorizing the Data

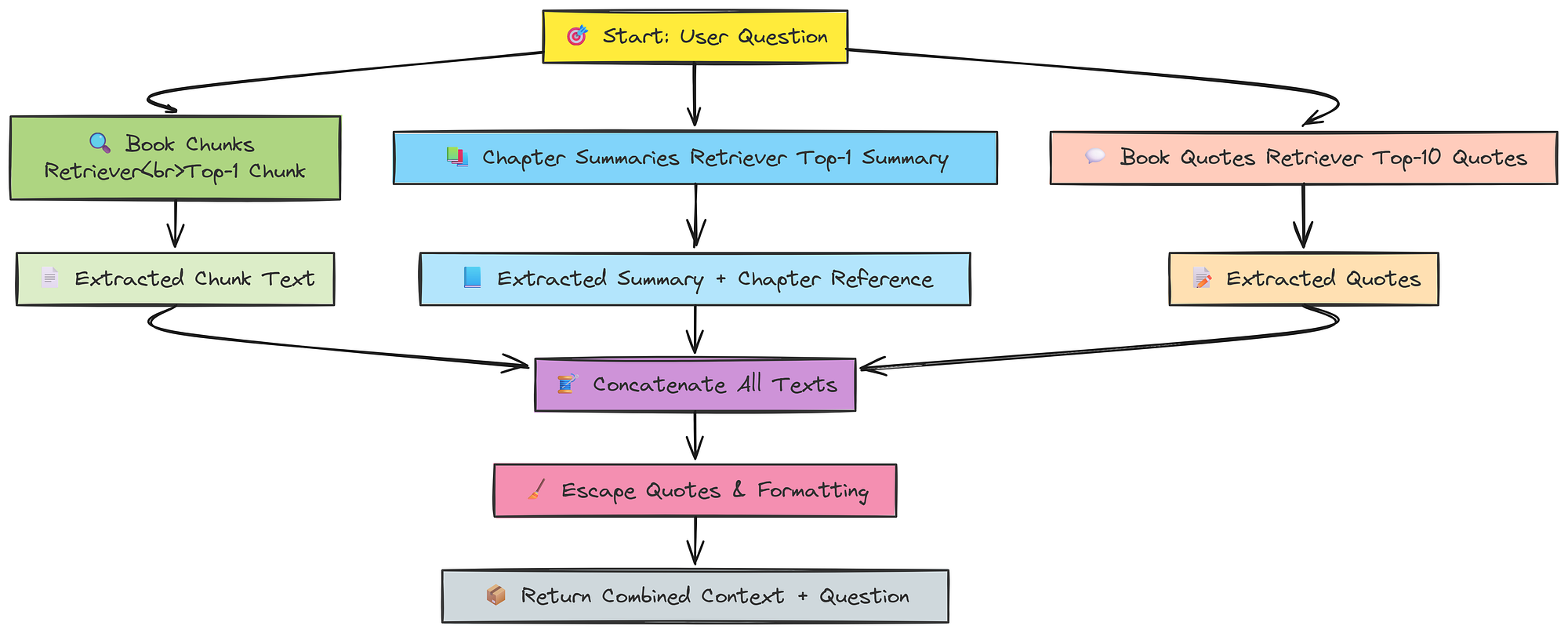

- Creating a Retriever for Context

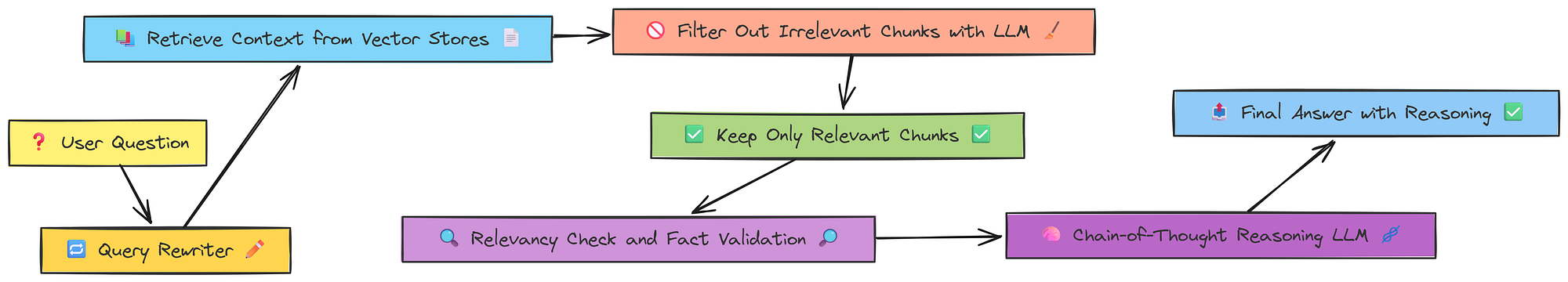

- A Filter for Irrelevant Information

- Query Rewriter

- Chain-of-Though (COT) Reasoning

- Relevancy Check and Grounded on Facts

- Testing our RAG Pipeline

- Visualizing our RAG Pipeline using LangGraph

- Sub Graph Approach and Distillation Grounding

- Creating Sub Graph for Retrieval and Distillation

- Creating Sub Graph to solve Hallucinations

- Creating and Testing Plan Executor

- Re-Planner Thinking Logic

- Creating Task Handler

- Anonymize/De-Anonymize the Input Question

- Compiling and Visualizing the RAG Pipeline

- Testing our Finalized Pipeline

- Evaluation using RAGAS

- Summarizing Everything

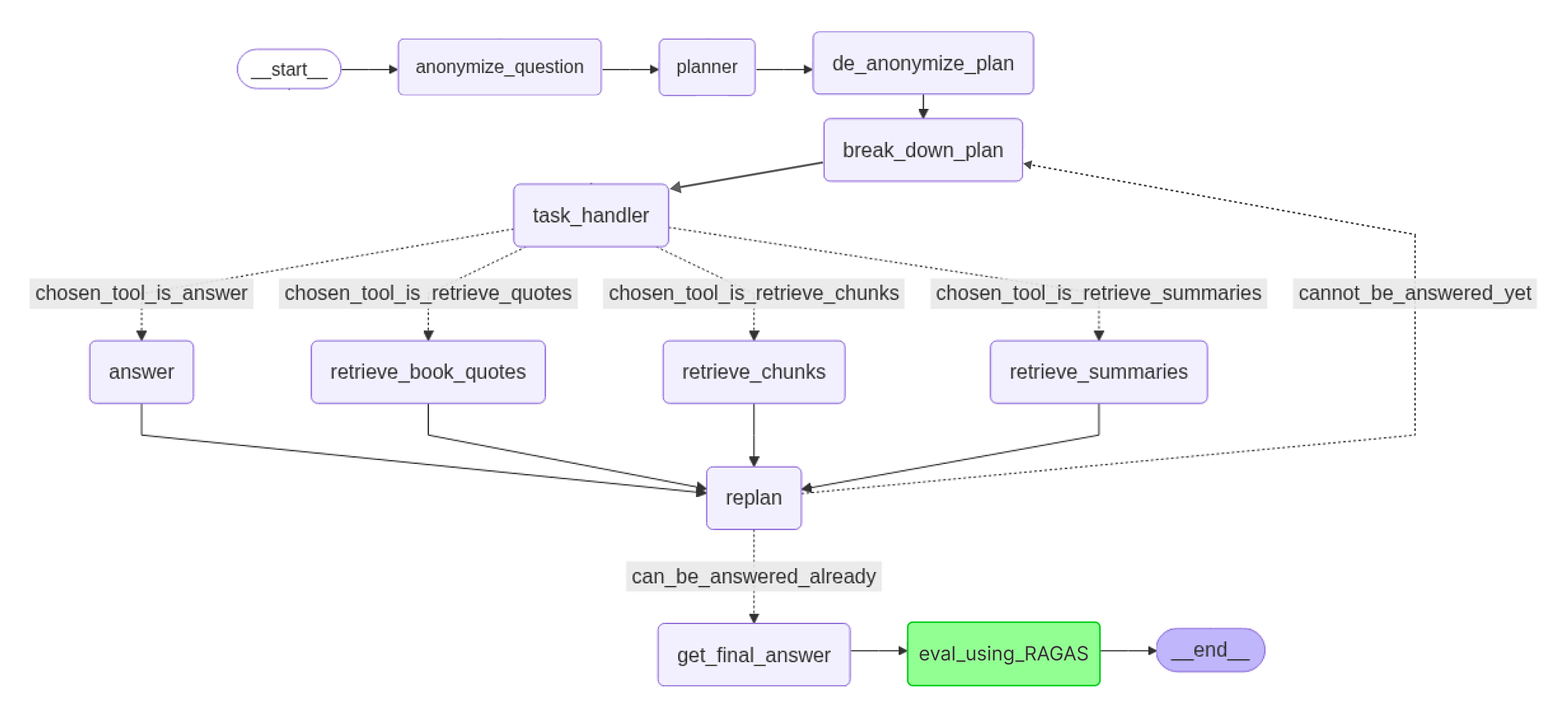

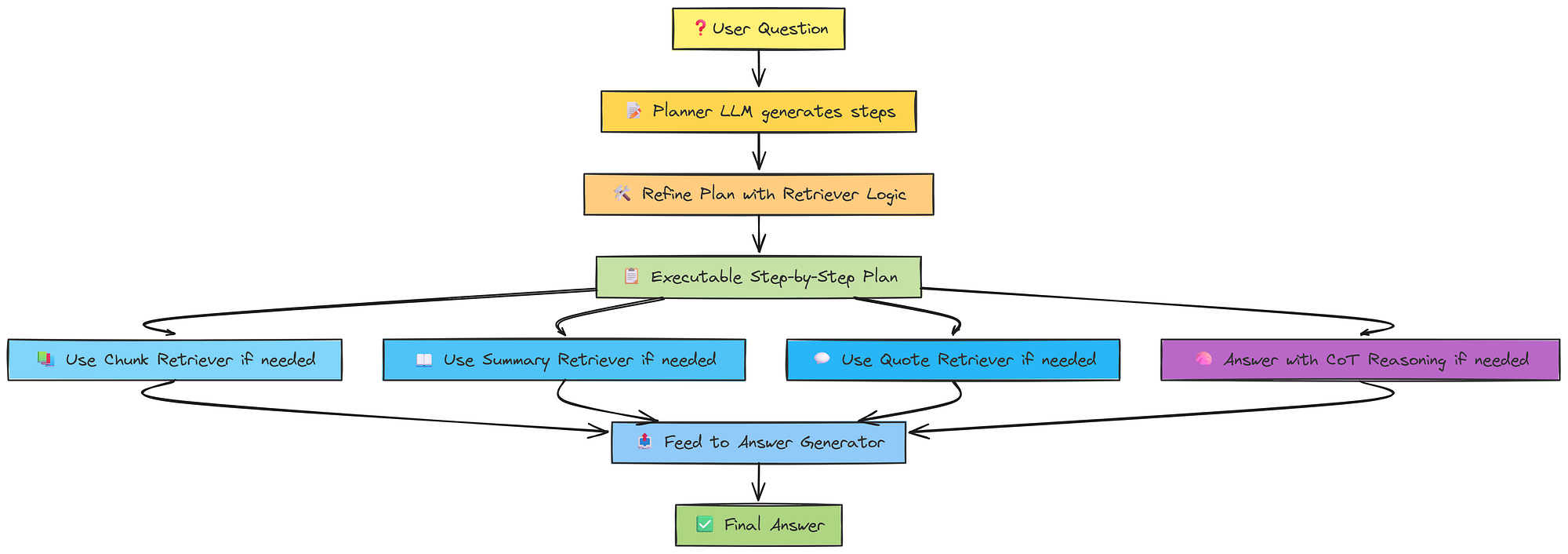

Before we start coding its better to visually see how our rag pipeline looks, when we move further we will visualize each of the components of it.

First, we call anonymize_question. This replaces specific names (e.g., "Harry Potter", "Voldemort") with placeholders (Person X, Villain Y) to avoid bias from the LLM pre-trained knowledge.

Next, the planner builds a high-level strategy. For a question like "How did X defeat Y?", it might plan:

- Identify

XandY - Locate their final confrontation

- Analyze

Xactions - Draft an answer

We then run de_anonymize_plan, restoring original names to make the plan specific and usable. The updated plan goes to break_down_plan, which turns each high-level step into concrete tasks.

The task_handler then selects the right tool for each task. Options include:

chosen_tool_is_retrieve_quotes: Finds specific quotes or dialoguechosen_tool_is_retrieve_chunks: Gets general info and contextchosen_tool_is_retrieve_summaries: Summarizes entire chapterschosen_tool_is_answer: Answers directly when enough context exists

After using a retrieval tool (retrieve_book_quotes, retrieve_chunks, or retrieve_summaries), new info is sent to replan.

replan reviews progress, goals, and new input to decide whether to update or extend the plan.

This cycle task_handler -> tool -> replan repeats until the system decides the question can_be_answered_already. Then, get_final_answer synthesizes all the evidence into a complete response.

Finally, eval_using_RAGAS checks the answer for accuracy and source faithfulness. If it passes, the process ends with __end__, delivering a verified, well-reasoned answer.

So, LangChain, LangGraph all these modules for creating a RAG system are an entire architecture.

So we will only import modules when they are needed, as it will help us learn in a proper way.

The very first step is to create environment variables that will hold our sensitive info like API keys and other such things.

# Set the OpenAI API key from environment variable (for use by OpenAI LLMs)

# os.environ["OPENAI_API_KEY"] = os.getenv('OPENAI_API_KEY')

# Set the OpenAI API key from environment variable (for use by OpenAI LLMs)

os.environ["TOGETHER_API_KEY"] = os.getenv('TOGETHER_API_KEY')

# Retrieve the Groq API key from environment variable (for use by Groq LLMs)

groq_api_key = os.getenv('GROQ_API_KEY')We are using two AI model providers here. Together AI offers open-source models, which are widely used in most RAG setups to make them cost-efficient, as open-source models are generally cheaper.

Both Groq and Together AI provide free credits, which should be sufficient to explore and follow along with this blog and much more.

Groq structures the output very well. However, if you can improve your prompt templates to guide the LLM toward structured outputs, you could potentially skip using Groq altogether. In that case, you can rely solely on Together AI or even Hugging Face local LLMs, especially since LangChain is an ecosystem with extensive feature support.

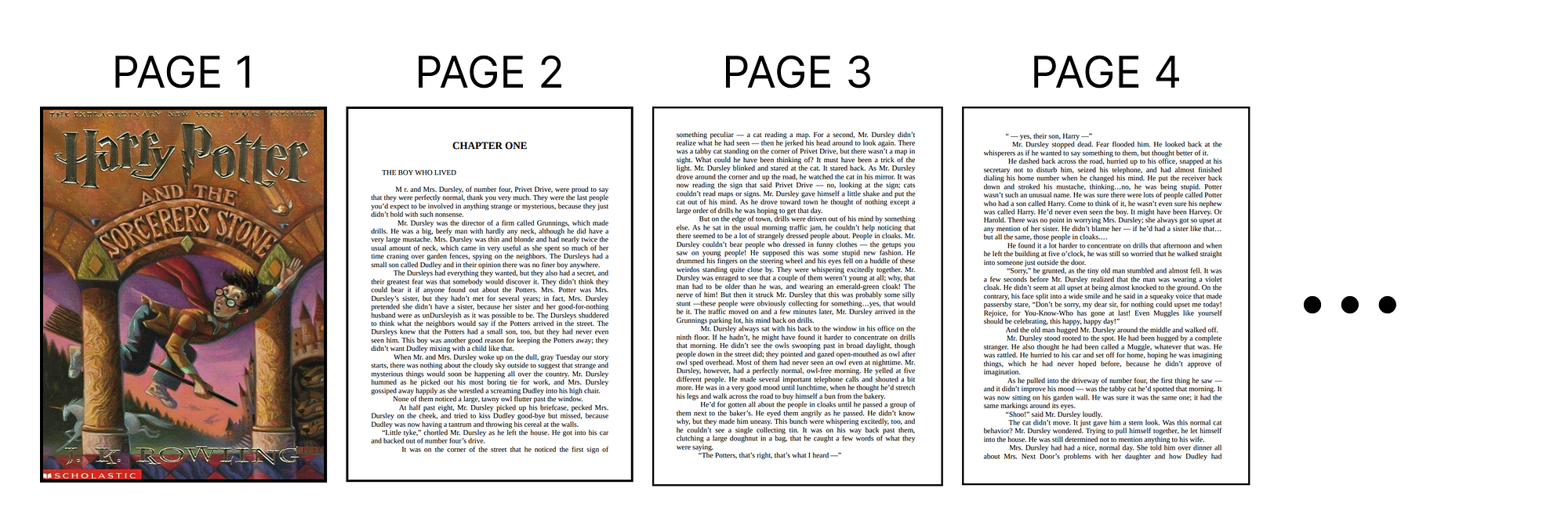

To start, we need to have a dataset. A RAG pipeline is typically created using large amounts of raw text data, usually in PDF, CSV, or TXT formats. However, the challenge with text data is that they often require extensive cleaning, as each file may need a different approach.

We will use the Harry Potter books, which resemble a real-world scenario due to various string formatting issues they contain. You can download the book from here. Once downloaded, we can begin the initial step, breaking down the document.

Let’s define the PDF path.

# Our Data Path (Harry Potter Book)

book_path ="Harry Potter - Book 1 - The Sorcerers Stone.pdf"The most important step before we preprocess or clean our data for RAG is to split the document logically and traditionally.

In our case, the PDF consists of different chapters, which is the best way to split our storybook logically, so let’s do that.

First, we need to load our PDF into a single, consolidated text.

import re

import PyPDF2

from langchain.docstore.document import Document

# Open and read the PDF file in binary mode

with open(book_path, 'rb') as pdf_file:

# Create a PDF reader object

pdf_reader = PyPDF2.PdfReader(pdf_file)

# Extract text from all pages and join into a single string

full_text = " ".join([page.extract_text() for page in pdf_reader.pages])Now that we have decided to split the PDF based on chapters, we can use a regex pattern to do that. So, let’s define the pattern.

# Split the text into sections using chapter headers as delimiters

# Regex pattern matches "CHAPTER" followed by uppercase words

chapter_sections = re.split(r'(CHAPTER\s[A-Z]+(?:\s[A-Z]+)*)', full_text)Using this regex pattern, we can easily split our full-text PDF into several chapters.

# Create Document objects for each chapter

chapters = []

# Iterate through sections in pairs (header + content)

for i in range(1, len(chapter_sections), 2):

# Combine chapter header with its content

chapter_text = chapter_sections[i] + chapter_sections[i + 1]

# Create a Document with chapter text and metadata

doc = Document(page_content=chapter_text, metadata={"chapter": i // 2 + 1})

chapters.append(doc)Let’s print the total number of chapters along with a sample of the chapter content.

# Total number of chapters extracted

print(f"Total number of chapters extracted: {len(chapters)}")

#### OUTPUT ####

Total number of chapters extracted: 17So, we have a total of 17 chapters from our PDF. However, we typically don’t rely on just one breakpoint, it’s better to focus on 3 to 4 or more breakpoints that capture important information within each chunk.

In our book, quotes serve as the second most important breakpoint, as they often summarize key information. In the case of financial documents, important breakpoints might include tables or financial statements, since they contain critical data.

So, let’s break down our document into a new logical chunking based on quotes.

# Define the regex pattern to find quotes longer than min_length characters.

# re.DOTALL allows '.' to match newline characters.

quote_pattern_longer_than_min_length = re.compile(rf'"(.{{{min_length},}}?)"', re.DOTALL)

# Initialize an empty list to store the quote documents

book_quotes_list = []

min_length = 50

# Iterate through each chapter document to find and extract quotes

for doc in tqdm(chapters, desc="Extracting quotes"):

content = doc.page_content

# Find all occurrences that match the quote pattern

found_quotes = quote_pattern_longer_than_min_length.findall(content)

# For each found quote, create a Document object and add it to the list

for quote in found_quotes:

quote_doc = Document(page_content=quote)

book_quotes_list.append(quote_doc)Let’s print the total number of quotes along with a sample quote to see how it looks.

# Total number of quotes

print(f"Total number of quotes extracted: {len(book_quotes_list)}")

# Print a random quote's content

print(f"Random quote content: {book_quotes_list[5].page_content[:500]}...")

#### OUTPUT ####

Total number of quotes extracted: 1337

Random quote content: Most mysterious. And now, over to JimMcGuffin ...We have extracted a total of approximately 1,300 quotes from our book. Now, there’s one more common method to break down our data that is chunking, which is the simplest and most widely used approach by developers. Let’s proceed with that.

from langchain.text_splitter import RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter

chunk_size = 1000 # Size of each chunk in characters

chunk_overlap = 200 # Number of characters to overlap between chunks

# Create a text splitter that splits documents into chunks of specified size with overlap

text_splitter = RecursiveCharacterTextSplitter(

chunk_size=chunk_size, chunk_overlap=chunk_overlap, length_function=len

)

# Split the cleaned documents into smaller chunks for downstream processing (e.g., embedding, retrieval)

document_splits = text_splitter.split_documents(documents)We can simply chunk the data, but LangChain offers a TextSplitter for chunking with many additional features.

To enhance the chunking process, we have used the Recursive Character TextSplitter, which creates overlapping chunks. This overlap makes each chunk maintains some contextual relationship with the previous one.

print(f"Number of documents after splitting: {len(document_splits)}")

#### OUTPUT ####

Number of documents after splitting: 612So, total number of chunks we have is 612 and we have broken our data in logical ways such as chapters and quotes as well as the traditional method of chunking. Now, it’s time to start cleaning it.

Looking at a sample chapter, we notice extra spaces between letters, which is problematic. So, let’s use regex to remove those and eliminate any special characters from the text.

# Print the first chapter's content and metadata

print(f"First chapter content: {chapters[0].page_content[:500]}...")

#### OUTPUT ####

First chapter content: CHAPTER ONE

THE BOY WHO LIVED

M

r. and M r s. D u r s l e y , o f n u m b e r ...These extra spaces between characters are called \t tab spaces. We need to remove them first.

# Pre-compile the regular expression for finding tab characters for efficiency

tab_pattern = re.compile(r'\t')

# Iterate through each chapter document to clean its content

for doc in chapters:

# Replace tab characters ('\t') with a single space (' ') using the pre-compiled regex.

# This is a data cleaning step to normalize whitespace for better processing later.

doc.page_content = tab_pattern.sub(' ', doc.page_content)Let’s print the updated output and see how it has changed.

# Print the first cleaned chapter's content and metadata

print(f"First cleaned chapter content: {chapters[0].page_content[:500]}...")

#### OUTPUT ####

First cleaned chapter content: CHAPTER ONE

THE BOY WHO LIVED

M

r. and Mrs. Dursley, of number f ....Though we have removed the extra spaces, you can still see that new lines exist in our data. This is not good, as it increases token count when passed to embedding models or LLMs.

So, we need to remove various types of new lines and unnecessary characters from our data.

# It is used to collapse multiple blank lines into a single one, improving text readability.

multiple_newlines_pattern = re.compile(r'\n\s*\n')

# This pattern identifies a word character followed by a newline, and then another word character.

# Its purpose is to locate and mend words that have been erroneously split across two lines.

word_split_newline_pattern = re.compile(r'(\w)\n(\w)')

# This pattern searches for one or more consecutive space characters.

# It is utilized to consolidate multiple spaces into a single space, ensuring consistent spacing.

multiple_spaces_pattern = re.compile(r' +')

# Iterate through each chapter document for further cleaning

for doc in chapters:

# 1. Replace multiple newlines with a single newline.

page_content = multiple_newlines_pattern.sub('\n', doc.page_content)

# 2. Remove newlines that are not followed by a space or another newline.

page_content = word_split_newline_pattern.sub(r'\1\2', page_content)

# 3. Replace any remaining single newlines (often within paragraphs) with a space.

page_content = page_content.replace('\n', ' ')

# 4. Reduce multiple spaces to a single space.

page_content = multiple_spaces_pattern.sub(' ', page_content)

doc.page_content = page_contentLet’s print the finalized, cleaned data.

# Print a random further cleaned chapter's content

print(f"First cleaned chapter content: {chapters[15].page_content[:500]}...")

#### OUTPUT ####

First cleaned chapter content:

THE BOY WHO LIVED

Mr. and Mrs. Dursley, of number f ....It’s in much better form now. In a similar way we can cleaned our traditional chunked data also.

# Perform all previous regular cleaning steps on the chunked documents

for doc in document_splits:

# Replace tab characters with a single space

doc.page_content = tab_pattern.sub(' ', doc.page_content)

# Collapse multiple newlines into a single newline

doc.page_content = multiple_newlines_pattern.sub('\n', doc.page_content)

# Fix word splits across newlines (e.g., "mag-\nic" -> "magic")

doc.page_content = word_split_newline_pattern.sub(r'\1\2', doc.page_content)

# Collapse multiple spaces into a single space

doc.page_content = multiple_spaces_pattern.sub(' ', doc.page_content)We have reduced as many unnecessary characters as possible. Let’s proceed with some analysis on our data.

# Calculate the word count for each chapter by splitting the page_content on whitespace

chapter_word_counts = [len(doc.page_content.split()) for doc in chapters]

# Find the maximum number of words in a chapter

max_words = max(chapter_word_counts)

# Find the minimum number of words in a chapter

min_words = min(chapter_word_counts)

# Calculate the average number of words per chapter

average_words = sum(chapter_word_counts) / len(chapter_word_counts)

# Print the statistics

print(f"Max words in a chapter: {max_words}")

print(f"Min words in a chapter: {min_words}")

print(f"Average words in a chapter: {average_words:.2f}")

#### OUTPUT ####

Max words in a chapter: 6343

Min words in a chapter: 2915

Average words in a chapter: 4402.18The maximum number of words in a chapter is around 6K. This analysis, while not important in our current case, can be important because the LLM context window is highly sensitive to the input it receives. This can affect our approach.

For now, we are in a good position since our chapter word counts are well below the context limits of most LLMs. However, we will still account for scenarios where this might fail.

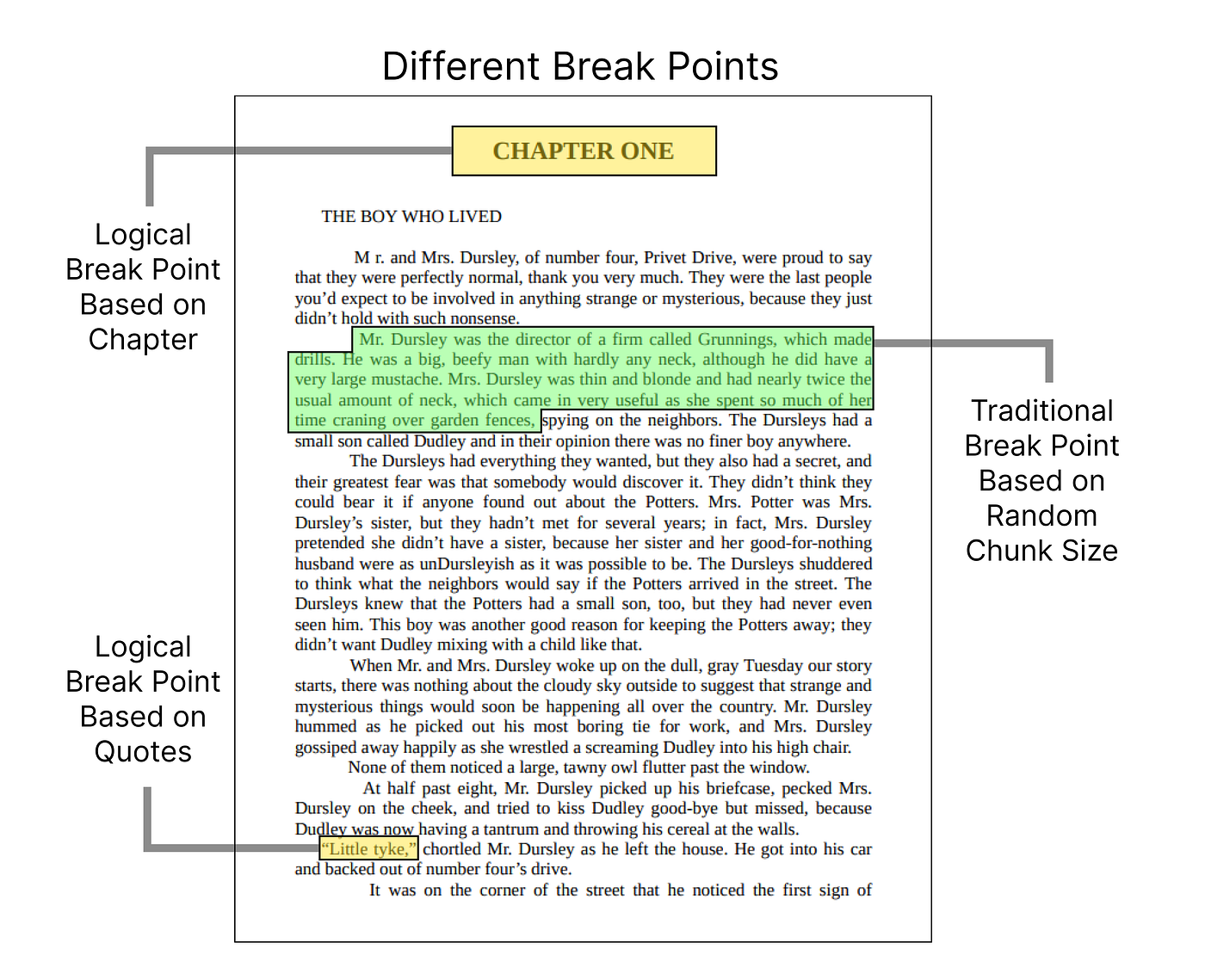

Our quotes data is already quite small, as it only contains key quotes that are typically short. However, the chapters are quite large, and since the Harry Potter books include a lot of unnecessary information such as regular conversation, we can restructure them to further reduce their size.

To do this, we can use LLMs to extensively summarize the chapters, it will contain the important and relevant information.

from langchain.prompts import PromptTemplate

# Create a prompt template for text summarization

# This template defines the structure for generating summaries

template = """Write an extensive summary of the following:

{text}

SUMMARY:"""

# Initialize the PromptTemplate with the template and input variables

# The template expects one input variable called "text"

summarization_prompt = PromptTemplate(

template=template,

input_variables=["text"]

)Let’s use DeepSeek V3 to create summaries for each chapter now.

# Initialize the summarization chain

chain = load_summarize_chain(deepseek_v3, chain_type="stuff", prompt=summarization_prompt)

# Initialize a list to store the summaries

chapter_summaries = []

# Iterate through each chapter to generate a summary

for chapter in chapters:

# Generate summary using the chain

summary = chain.invoke([chapter])

# Clean the output text

cleaned_text = re.sub(r'\n\n', '\n', summary["output_text"])

# Create a Document object for the summary, preserving the original metadata

doc_summary = Document(page_content=cleaned_text, metadata=chapter.metadata)

chapter_summaries.append(doc_summary)The chain_type used here is stuff. We use it because, in our case, the maximum number of words in a chapter is around 6K, which is well within the context length of most LLMs, including DeepSeek-V3.

However, in other scenarios where the input length might exceed the model’s context window, choosing a different chain_type becomes necessary:

- stuff: Concatenates all documents into a single prompt and summarizes them in one go.

- map_reduce: Summarizes documents individually (“map”) and then combines those summaries into a final one (“reduce”).

- refine: Creates an initial summary and then incrementally improves it by refining with each additional document.

Now that we have restructured our dataset, we can now vectorize and store it.

In our Setting Up the Environment section, we initialize several models along with an embedding model, specifically the ML2 BERT model with a 32k context window.

For storing the data, FAISS is one of the most popular frameworks from Meta, known for its high efficiency in improving similarity search.

It is also used by many other popular frameworks like Qdrant, Pinecone, and more. So, let’s vectorize our data and then store it in a vectorstore database.

from langchain.vectorstores import FAISS

# Create a FAISS vector store from the document splits using the embedding model

book_splits_vectorstore = FAISS.from_documents(document_splits, m2_bert_80M_32K)

# Create a FAISS vector store from the chapter summaries using the embedding model

chapter_summaries_vectorstore = FAISS.from_documents(chapter_summaries, m2_bert_80M_32K)

# Create a FAISS vector store from the quotes using the embedding model

quotes_vectorstore = FAISS.from_documents(book_quotes_list, m2_bert_80M_32K)So we have three different breakpoint dataset available we have converted all of them into a vectorize data we can further save this database locally also for example to stores quotes data wer can use like.

# Save the quote vector store locally for later use

quotes_vectorstore.save_local("quotes_vectorstore")and then you can observe a local folder got created in your current directorywith this name that folder then can be used to later call the vectorize embeddings using

# This allows for efficient similarity search over the book quotes using the specified embedding model.

quotes_vectorstore = FAISS.load_local(

"quotes_vectorstore", # Path to the saved FAISS index for quotes

m2_bert_80M_32K, # Embedding model used for encoding queries and documents

allow_dangerous_deserialization=True # Allows loading objects that may not be fully secure (required for FAISS)

)This vector database can then be easily push on different cloud database platforms as many cloud vector databases do supports FAISS. Now that we have vectorize we need to go for creating a logical pipeline for a rag chatbot.

The very first step of our core RAG pipeline is to create a retriever that can fetch the correct chunks from each of our datasets (chapter summaries, quotes, traditional chunk data). But first, we need to transform our vectorized data into a retriever.

# Retriever for book content chunks (splits), returns the top 1 most relevant chunk.

book_chunks_retriever = book_splits_vectorstore.as_retriever(search_kwargs={"k": 1})

# Retriever for chapter summaries, returns the top 1 most relevant summary.

chapter_summaries_retriever = chapter_summaries_vectorstore.as_retriever(search_kwargs={"k": 1})

# Retriever for book quotes, returns the top 10 most relevant quotes.

book_quotes_retriever = quotes_vectorstore.as_retriever(search_kwargs={"k": 10})I have set the top-k value to 1 for summaries and traditional chunks. However, for book quotes, which are much shorter, I set it to 10 to retrieve more relevant information. Now, we need to write our retriever function using these settings.

def retrieve_context_per_question(state):

"""

Retrieves relevant context for a given question. The context is retrieved from the book chunks,

chapter summaries, and book quotes using their respective retrievers.

Args:

state: A dictionary containing the question to answer.

"""

# Retrieve relevant book content chunks

print("Retrieving relevant chunks...")

question = state["question"]

docs = book_chunks_retriever.get_relevant_documents(question)

# Concatenate the content of the retrieved book chunks

context = " ".join(doc.page_content for doc in docs)

# Retrieve relevant chapter summaries

print("Retrieving relevant chapter summaries...")

docs_summaries = chapter_summaries_retriever.get_relevant_documents(state["question"])

# Concatenate chapter summaries with chapter citation

context_summaries = " ".join(

f"{doc.page_content} (Chapter {doc.metadata['chapter']})" for doc in docs_summaries

)

# Retrieve relevant book quotes

print("Retrieving relevant book quotes...")

docs_book_quotes = book_quotes_retriever.get_relevant_documents(state["question"])

book_qoutes = " ".join(doc.page_content for doc in docs_book_quotes)

# Concatenate all contexts together: book chunks, chapter summaries, and quotes

all_contexts = context + context_summaries + book_qoutes

# Escape quotes for downstream processing

all_contexts = all_contexts.replace('"', '\\"').replace("'", "\\'")

# Return the combined context and the original question

return {"context": all_contexts, "question": question}So, this is our first function in this guide. It uses a very simple approach to retrieve relevant documents and merge them into a combined context, which can then be passed to the next step.

A bit of cleaning is also performed, such as removing escape characters and similar formatting issues.

But when we retrieve relevant information, we also need a filter to remove any irrelevant content. There are many ways to implement filtering, but using LLMs is one of the most common and effective approaches.

First, we need to define a prompt template that guides the LLM on what to do. So, let’s go ahead and define that.

# Define a prompt template for filtering out non-relevant content from retrieved documents.

keep_only_relevant_content_prompt_template = """

You receive a query: {query} and retrieved documents: {retrieved_documents} from a vector store.

You need to filter out all the non-relevant information that does not supply important information regarding the {query}.

Your goal is to filter out the non-relevant information only.

You can remove parts of sentences that are not relevant to the query or remove whole sentences that are not relevant to the query.

DO NOT ADD ANY NEW INFORMATION THAT IS NOT IN THE RETRIEVED DOCUMENTS.

Output the filtered relevant content.

"""Now we can use this prompt template to initialize our relevancy checker model. In this case, we are using the LLaMA 3.3 70B model.

from langchain_core.pydantic_v1 import BaseModel, Field

# Define a Pydantic model for structured output from the LLM, specifying that the output should contain only the relevant content.

class KeepRelevantContent(BaseModel):

relevant_content: str = Field(description="The relevant content from the retrieved documents that is relevant to the query.")

# Create a prompt template for filtering only the relevant content from retrieved documents, using the provided template string.

keep_only_relevant_content_prompt = PromptTemplate(

template=keep_only_relevant_content_prompt_template,

input_variables=["query", "retrieved_documents"],

)

# This model will be used to extract only the content relevant to a given query from retrieved documents.

keep_only_relevant_content_llm = ChatTogether(

temperature=0,

model_name="meta-llama/Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo-Free",

api_key=together_api_key,

max_tokens=2000

)

# Create a chain that combines the prompt template, the LLM, and the structured output parser.

# The chain takes a query and retrieved documents, filters out non-relevant information,

# and returns only the relevant content as specified by the KeepRelevantContent Pydantic model.

keep_only_relevant_content_chain = (

keep_only_relevant_content_prompt

| keep_only_relevant_content_llm.with_structured_output(KeepRelevantContent)

)We also need to wrap our relevancy checker chain into a dedicated function that can structurally respond with which chunks are relevant to the given query and which ones are not.

from pprint import pprint

def keep_only_relevant_content(state):

"""

Filters and retains only the content from the retrieved documents that is relevant to the query.

Args:

state (dict): A dictionary containing:

- "question": The user's query.

- "context": The retrieved documents/content as a string.

Returns:

dict: A dictionary with:

- "relevant_context": The filtered relevant content as a string.

- "context": The original context.

- "question": The original question.

"""

question = state["question"]

context = state["context"]

# Prepare input for the LLM chain

input_data = {

"query": question,

"retrieved_documents": context

}

print("keeping only the relevant content...")

pprint("--------------------")

# Invoke the LLM chain to filter out non-relevant content

output = keep_only_relevant_content_chain.invoke(input_data)

relevant_content = output.relevant_content

# Ensure the result is a string (in case it's not)

relevant_content = "".join(relevant_content)

# Escape quotes for downstream processing

relevant_content = relevant_content.replace('"', '\\"').replace("'", "\\'")

return {

"relevant_context": relevant_content,

"context": context,

"question": question

}We can now add a key-value parameter next to each retrieved chunk to indicate whether it is relevant or not.

One of the challenge with RAG is that user query is not descriptive enough to fetch relevant content, so one approach to reduce this issue is to let LLM rewrite the query first in order to have relevant content being fetched so let’s do that.

In a similar we created a chain for filtering step we can do the same here create a chain for query rewriting.

from langchain_core.output_parsers import JsonOutputParser

# Define the output schema for the rewritten question using Pydantic BaseModel

class RewriteQuestion(BaseModel):

"""

Output schema for the rewritten question.

"""

rewritten_question: str = Field(

description="The improved question optimized for vectorstore retrieval."

)

explanation: str = Field(

description="The explanation of the rewritten question."

)

# Create a JSON output parser for the RewriteQuestion schema

rewrite_question_string_parser = JsonOutputParser(pydantic_object=RewriteQuestion)

# Initialize the LLM for rewriting questions using Groq's Llama3-70B model

rewrite_llm = ChatGroq(

temperature=0,

model_name="llama3-70b-8192",

groq_api_key=groq_api_key,

max_tokens=4000

)Ten we can define the prompt template and initialize the query rewriting component of our rag solution

# Define the prompt template for question rewriting

rewrite_prompt_template = """You are a question re-writer that converts an input question to a better version optimized for vectorstore retrieval.

Analyze the input question {question} and try to reason about the underlying semantic intent / meaning.

{format_instructions}

"""

# Create the prompt with input and partial variables

rewrite_prompt = PromptTemplate(

template=rewrite_prompt_template,

input_variables=["question"],

partial_variables={"format_instructions": rewrite_question_string_parser.get_format_instructions()},

)

# Combine the prompt, LLM, and output parser into a runnable chain

question_rewriter = rewrite_prompt | rewrite_llm | rewrite_question_string_parserWe also need a function that can simply return the structured response just like we see earlier in our filtering step.

def rewrite_question(state):

"""

Rewrites the given question using the question_rewriter LLM chain.

Args:

state (dict): A dictionary containing the key "question" with the question to rewrite.

Returns:

dict: A dictionary with the rewritten question under the key "question".

"""

question = state["question"]

print("Rewriting the question...")

# Invoke the question_rewriter chain to get the improved question

result = question_rewriter.invoke({"question": question})

new_question = result["rewritten_question"]

return {"question": new_question}This will return our rewritten question. Now, we move on to the next step.

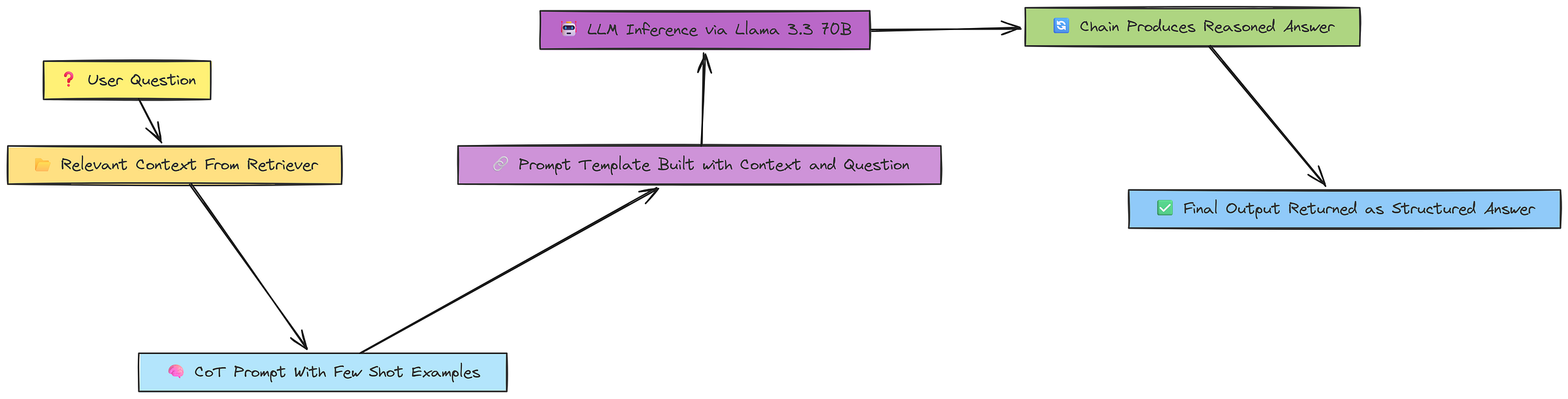

Instead of asking the LLM to answer the question directly, we can use a better approach that reasons through the answer using a multi-step method known as the chaining approach (Chain of Thought or CoT).

We are going to implement this in a similar manner to how we previously coded our other components.

# Define a Pydantic model for the output of the answer generation chain.

class QuestionAnswerFromContext(BaseModel):

answer_based_on_content: str = Field(

description="Generates an answer to a query based on a given context."

)

# Initialize the LLM for answering questions from context using Together's Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo-Free model.

question_answer_from_context_llm = ChatTogether(

temperature=0,

model_name="meta-llama/Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo-Free",

api_key=together_api_key,

max_tokens=2000

)But the important part is the prompt template, which guides the LLM to reason through the answer using a step-by-step approach. So, let’s create that prompt template for this purpose.

question_answer_cot_prompt_template = """

Chain-of-Thought Reasoning Examples

Example 1

Context: Mary is taller than Jane. Jane is shorter than Tom. Tom is the same height as David.

Question: Who is the tallest person?

Reasoning:

Mary > Jane

Jane < Tom → Tom > Jane

Tom = David

So: Mary > Tom = David > Jane

Final Answer: Mary

Example 2

Context: Harry read about three spells—one turns people into animals, one levitates objects, and one creates light.

Question: If Harry cast these spells, what could he do?

Reasoning:

Spell 1: transform people into animals

Spell 2: levitate things

Spell 3: make light

Final Answer: He could transform people, levitate objects, and create light

Example 3

Context: Harry Potter got a Nimbus 2000 broomstick for his birthday.

Question: Why did Harry receive a broomstick?

Reasoning:

The context says he received a broomstick

It doesn’t explain why or who gave it

No info on hobbies or purpose

Final Answer: Not enough context to know why he received it

Now, follow the same pattern below.

Context:

{context}

Question:

{question}

"""LLMs can produce different reasoning styles with each run, which can lead to inconsistency in Chain of Thought (CoT) responses.

To address this, we can use a few-shot CoT approach, where we provide the LLM with multiple examples demonstrating the desired response structure and reasoning style. This is exactly what we have implemented so far.

# Create a prompt template for answering questions from context using chain-of-thought reasoning.

question_answer_from_context_cot_prompt = PromptTemplate(

template=question_answer_cot_prompt_template, # Uses examples and instructions for step-by-step reasoning

input_variables=["context", "question"], # Expects 'context' and 'question' as inputs

)

# Create a chain that combines the prompt, the LLM, and the structured output parser.

# This chain will generate an answer with reasoning, given a context and a question.

question_answer_from_context_cot_chain = (

question_answer_from_context_cot_prompt

| question_answer_from_context_llm.with_structured_output(QuestionAnswerFromContext)

)And after that, we can create a function on top of it to return the response in a structured format, just as we have been doing previously.

def answer_question_from_context(state):

"""

Answers a question from a given context using a chain-of-thought LLM chain.

Args:

state (dict): A dictionary containing:

- "question": The query question.

- "context": The context to answer the question from.

- Optionally, "aggregated_context": an aggregated context to use instead.

Returns:

dict: A dictionary with:

- "answer": The generated answer.

- "context": The context used.

- "question": The original question.

"""

# Extract the question from the state

question = state["question"]

# Use "aggregated_context" if present, otherwise use "context"

context = state["aggregated_context"] if "aggregated_context" in state else state["context"]

# Prepare input for the LLM chain

input_data = {

"question": question,

"context": context

}

print("Answering the question from the retrieved context...")

# Invoke the chain-of-thought LLM chain to generate an answer

output = question_answer_from_context_cot_chain.invoke(input_data)

answer = output.answer_based_on_content

print(f'answer before checking hallucination: {answer}')

# Return the answer, context, and question in a dictionary

return {"answer": answer, "context": context, "question": question}Great! So far, we have implemented the retriever, irrelevant checker, query rewriter, and CoT chain. Now, we need to validate whether the documents being fetched are truly relevant.

This is a two-step approach, we have already removed clearly irrelevant documents, and now we will perform a secondary relevancy check on the remaining ones to make the RAG pipeline more efficient and precise.

Once we have the filtered relevant documents, we need to further check their ground truth relevancy and traditional relevancy.

This simply involves asking the LLM whether the content of each document is relevant to the rewritten query. The approach remains the same as before, using a prompt-based method to evaluate relevancy, just like we did in the earlier stages of the pipeline.

# Define a Pydantic model for the relevance output schema

class Relevance(BaseModel):

is_relevant: bool = Field(description="Whether the document is relevant to the query.")

explanation: str = Field(description="An explanation of why the document is relevant or not.")

# Create a JSON output parser for the Relevance schema

is_relevant_json_parser = JsonOutputParser(pydantic_object=Relevance)

# Initialize the LLM for relevance checking using Groq's Llama3-70B model

is_relevant_llm = ChatGroq(

temperature=0,

model_name="llama3-70b-8192",

groq_api_key=groq_api_key,

max_tokens=2000

)

# Define the prompt template for relevance checking

is_relevant_content_prompt = PromptTemplate(

template=is_relevant_content_prompt_template,

input_variables=["query", "context"],

partial_variables={"format_instructions": is_relevant_json_parser.get_format_instructions()},

)

# Combine the prompt, LLM, and output parser into a runnable chain

is_relevant_content_chain = is_relevant_content_prompt | is_relevant_llm | is_relevant_json_parserWe can use this chain in a traditional relevancy checker function, which will then return the output in a structured format.

def is_relevant_content(state):

"""

Determines if the document is relevant to the query.

Args:

state: A dictionary containing:

- "question": The query question.

- "context": The context to determine relevance.

"""

# Extract the question and context from the state dictionary

question = state["question"]

context = state["context"]

# Prepare the input data for the relevance checking chain

input_data = {

"query": question,

"context": context

}

# Invoke the chain to determine if the document is relevant

output = is_relevant_content_chain.invoke(input_data)

print("Determining if the document is relevant...")

# Check the output and return the appropriate label

if output["is_relevant"] == True:

print("The document is relevant.")

return "relevant"

else:

print("The document is not relevant.")

return "not relevant"In a similar way, we can check the grounded truth of the query using the context that will be passed to the LLM.

For this, we also need a prompt template that can evaluate the factual consistency between the query and the provided context, and return a simple “yes” or “no” based on whether the information aligns correctly.

# Define the output schema for fact-checking using Pydantic

class is_grounded_on_facts(BaseModel):

"""

Output schema for fact-checking if an answer is grounded in the provided context.

"""

grounded_on_facts: bool = Field(description="Answer is grounded in the facts, 'yes' or 'no'")

# Initialize the LLM for fact-checking using Together's Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo-Free model

is_grounded_on_facts_llm = ChatTogether(

temperature=0,

model_name="meta-llama/Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo-Free",

api_key=together_api_key,

max_tokens=2000

)

# Define the prompt template for fact-checking

is_grounded_on_facts_prompt_template = """You are a fact-checker that determines if the given answer {answer} is grounded in the given context {context}

you don't mind if it doesn't make sense, as long as it is grounded in the context.

output a json containing the answer to the question, and appart from the json format don't output any additional text.

"""

# Create the prompt object

is_grounded_on_facts_prompt = PromptTemplate(

template=is_grounded_on_facts_prompt_template,

input_variables=["context", "answer"],

)

# Build the chain: prompt -> LLM -> structured output

is_grounded_on_facts_chain = (

is_grounded_on_facts_prompt

| is_grounded_on_facts_llm.with_structured_output(is_grounded_on_facts)

)We can create a simple function for the grounding chain as well, which will return “useful” or “no” based on the given query and its context.

def grade_generation_v_documents_and_question(state):

"""

Grades the answer: checks if it's grounded in the context and if the question can be fully answered.

Returns: "hallucination", "useful", or "not_useful".

"""

context = state["context"]

answer = state["answer"]

question = state["question"]

# Check if answer is grounded in the context

grounded = is_grounded_on_facts_chain.invoke({"context": context, "answer": answer}).grounded_on_facts

if not grounded:

print("The answer is hallucination.")

return "hallucination"

print("The answer is grounded in the facts.")

# Check if the question can be fully answered from the context

can_be_answered = can_be_answered_chain.invoke({"question": question, "context": context})["can_be_answered"]

if can_be_answered:

print("The question can be fully answered.")

return "useful"

else:

print("The question cannot be fully answered.")

return "not_useful"Now that we have implemented the core components, we can move on to testing our RAG pipeline with a simple question to see how it performs.

So far, we have coded the following components of our RAG pipeline:

- Retrieving the context

- Filtering out non-useful context documents

- Query rewriting

- Relevancy checking and ground truth fact checking

Let’s ask a simple question and see how it goes.

# Initialize the state with the question to answer

init_state = {"question": "who is fluffy?"}

# Step 1: Retrieve relevant context from the vector stores for the given question

context_state = retrieve_context_per_question(init_state)

# Step 2: Filter the retrieved context to keep only the content relevant to the question

relevant_content_state = keep_only_relevant_content(context_state)

# Step 3: Check if the filtered content is relevant to the question

is_relevant_content_state = is_relevant_content(relevant_content_state)

# Step 4: Generate an answer to the question using the relevant context

answer_state = answer_question_from_context(relevant_content_state)

# Step 5: Grade the generated answer for factual grounding and usefulness

final_answer = grade_generation_v_documents_and_question(answer_state)

# Print the final answer

print(answer_state["answer"])And this is the response we get.

Retrieving relevant chunks...

Retrieving relevant chapter summaries...

keeping only the relevant content...

--------------------

Determining if the document is relevant...

The document is relevant.

--------------------

Answering the question from the retrieved context...

answer before checking hallucination: Fluffy is a three-headed dog.

--------------------

Checking if the answer is grounded in the facts...

The answer is grounded in the facts.

--------------------

Determining if the question is fully answered...

The question can be fully answered.

Fluffy is a three-headed dog.

So, our query is: “Who is Fluffy?”. If you have watched Harry Potter, you do know that Fluffy is a fictional three-headed dog from the series.

Our RAG pipeline follows a step-by-step approach from retrieving relevant context, filtering documents, rewriting the query, checking relevancy, to grounding the final answer.

It correctly identified that Fluffy is indeed a three-headed dog, it shows that the pipeline is working as intended.

The approach we have coded so far might be easier to follow for some through reading, but visualizing the RAG pipeline makes it much easier to understand how all the components work together as a cohesive flow. So, let’s create a graph to represent this pipeline visually.

from typing import TypedDict

from langgraph.graph import END, StateGraph

from langchain_core.runnables.graph import MermaidDrawMethod

from IPython.display import display, Image

# Define the data structure for graph state

class QualitativeRetievalAnswerGraphState(TypedDict):

question: str; context: str; answer: str

# Initialize the workflow graph

wf = StateGraph(QualitativeRetievalAnswerGraphState)

# Add nodes: (name, processing function)

for n, f in [("retrieve", retrieve_context_per_question),

("filter", keep_only_relevant_content),

("rewrite", rewrite_question),

("answer", answer_question_from_context)]:

wf.add_node(n, f)

# Define graph flow

wf.set_entry_point("retrieve") # Start from retrieving context

wf.add_edge("retrieve", "filter") # Pass to filtering content

wf.add_conditional_edges("filter", is_relevant_content, {

"relevant": "answer", # If relevant → answer

"not relevant": "rewrite" # Else → rewrite question

})

wf.add_edge("rewrite", "retrieve") # Retry flow after rewriting

wf.add_conditional_edges("answer", grade_generation_v_documents_and_question, {

"hallucination": "answer", # Retry if hallucinated

"not_useful": "rewrite", # Rewrite if not useful

"useful": END # End if answer is good

})

# Compile and visualize the workflow

display(Image(wf.compile().get_graph().draw_mermaid_png(draw_method=MermaidDrawMethod.API)))This graph is quite easy to follow as it shows the process clearly, starting with retrieving the context, then filtering the relevant content, while also rewriting the query if needed to improve context retrieval. If the retrieved answer isn’t useful, we apply Chain of Thought (CoT) reasoning and ground truth checking to refine the final answer.

But as developers, we know that RAG isn’t as simple as it may appear. In real-world applications, especially when tackling complex user tasks, many challenges arise that can’t be solved through basic semantic similarity retrieval. This is where the sub-graph approach becomes valuable.

For tasks that require deeper reasoning or multi-step understanding, we can break down the main RAG pipeline into multiple sub-graphs, each responsible for a specific function like query rewriting, document filtering, factual verification, and reasoning. These sub-graphs then interact to form a more modular and scalable solution.

For the distillation step, we can follow the same pattern we used earlier:

- Create a prompt template

- Build a chain around it

- Wrap it in a function

Now, let’s start by creating the prompt template, which should follow a strict policy it must return only true or false based on whether the content is factually grounded or not.

# Prompt template for checking if distilled content is grounded in the original context

is_distilled_content_grounded_on_content_prompt_template = """

You receive some distilled content: {distilled_content} and the original context: {original_context}.

You need to determine if the distilled content is grounded on the original context.

If the distilled content is grounded on the original context, set the grounded field to true.

If the distilled content is not grounded on the original context, set the grounded field to false.

{format_instructions}

"""Now we can use this prompt template to create a chain.

# Pydantic model for the output schema

class IsDistilledContentGroundedOnContent(BaseModel):

grounded: bool = Field(

description="Whether the distilled content is grounded on the original context."

)

explanation: str = Field(

description="An explanation of why the distilled content is or is not grounded on the original context."

)

# Output parser for the LLM response

is_distilled_content_grounded_on_content_json_parser = JsonOutputParser(

pydantic_object=IsDistilledContentGroundedOnContent

)

# PromptTemplate for the LLM

is_distilled_content_grounded_on_content_prompt = PromptTemplate(

template=is_distilled_content_grounded_on_content_prompt_template,

input_variables=["distilled_content", "original_context"],

partial_variables={

"format_instructions": is_distilled_content_grounded_on_content_json_parser.get_format_instructions()

},

)

# LLM instance for the task

is_distilled_content_grounded_on_content_llm = ChatGroq(

temperature=0,

model_name="llama3-70b-8192",

groq_api_key=groq_api_key,

max_tokens=4000

)

# Chain that combines prompt, LLM, and output parser

is_distilled_content_grounded_on_content_chain = (

is_distilled_content_grounded_on_content_prompt

| is_distilled_content_grounded_on_content_llm

| is_distilled_content_grounded_on_content_json_parser

)We can use this chain to create the main distillation function that will definitely work on grounded data.

def is_distilled_content_grounded_on_content(state):

"""

Determines if the distilled content is grounded in the original context.

Args:

state (dict): A dictionary containing:

- "relevant_context": The distilled content to check.

- "context": The original context to compare against.

Returns:

str: "grounded on the original context" if grounded, otherwise "not grounded on the original context".

"""

pprint("--------------------")

print("Determining if the distilled content is grounded on the original context...")

# Extract distilled content and original context from state

distilled_content = state["relevant_context"]

original_context = state["context"]

# Prepare input for the LLM chain

input_data = {

"distilled_content": distilled_content,

"original_context": original_context

}

# Invoke the LLM chain to check grounding

output = is_distilled_content_grounded_on_content_chain.invoke(input_data)

grounded = output["grounded"]

# Return result based on grounding

if grounded:

print("The distilled content is grounded on the original context.")

return "grounded on the original context"

else:

print("The distilled content is not grounded on the original context.")

return "not grounded on the original context"We have added the distillation component to our RAG bot, we are ready to start coding the sub-graph approach to handle more complex tasks.

Now that we are moving on to creating sub-graphs, we need to define individual retriever functions for each of our data sources:

- Chapter summaries

- Quotes

- Traditional chunked data

Starting with chapter summaries, our goal is to create a separate function for the retriever, which can then be used to plot the graph.

def retrieve_chunks_context_per_question(state):

"""

Retrieves relevant context for a given question. The context is retrieved from the book chunks and chapter summaries.

Args:

state: A dictionary containing the question to answer.

"""

# Retrieve relevant documents

print("Retrieving relevant chunks...")

question = state["question"]

docs = book_chunks_retriever.get_relevant_documents(question)

# Concatenate document content

context = " ".join(doc.page_content for doc in docs)

context = context.replace('"', '\\"').replace("'", "\\'") # Escape quotes for downstream processing

return {"context": context, "question": question}This function is pretty simple, getting all context and cleaning it a bit. Next, in the same way, we can code the function for the other two retrievers as well.

def retrieve_summaries_context_per_question(state):

print("Retrieving relevant chapter summaries...")

question = state["question"]

docs_summaries = chapter_summaries_retriever.get_relevant_documents(state["question"])

# Concatenate chapter summaries with citation information

context_summaries = " ".join(

f"{doc.page_content} (Chapter {doc.metadata['chapter']})" for doc in docs_summaries

)

context_summaries = context_summaries.replace('"', '\\"').replace("'", "\\'") # Escape quotes for downstream processing

return {"context": context_summaries, "question": question}

def retrieve_book_quotes_context_per_question(state):

question = state["question"]

print("Retrieving relevant book quotes...")

docs_book_quotes = book_quotes_retriever.get_relevant_documents(state["question"])

book_qoutes = " ".join(doc.page_content for doc in docs_book_quotes)

book_qoutes_context = book_qoutes.replace('"', '\\"').replace("'", "\\'") # Escape quotes for downstream processing

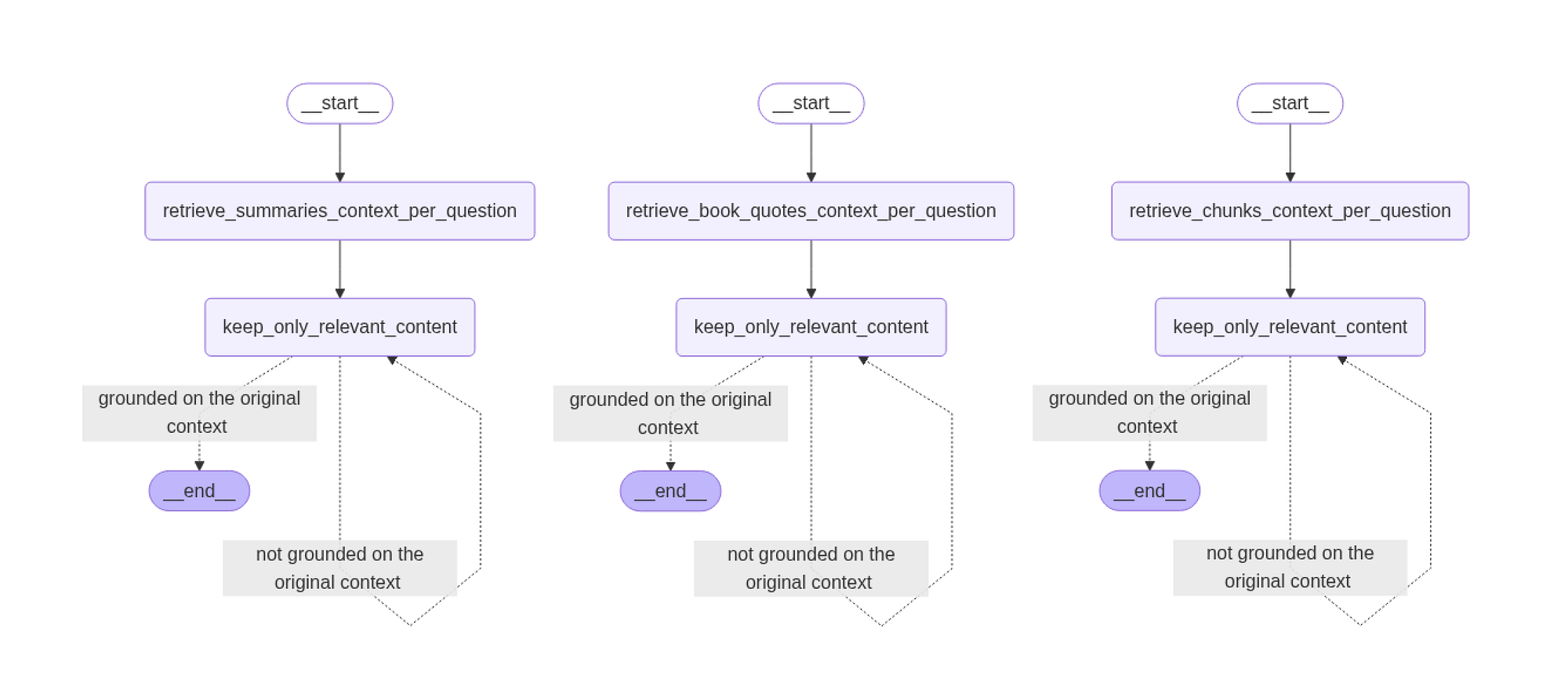

return {"context": book_qoutes_context, "question": question}The other two retriever functions return the same structured output, similar to our chapter summaries function. Now, let’s plot each of the retriever graphs side by side and see how they look.

class QualitativeRetrievalGraphState(TypedDict):

"""

Represents the state for qualitative retrieval workflows.

Attributes:

question (str): The input question to retrieve context for.

context (str): The original retrieved context from the source (e.g., book chunks, summaries, or quotes).

relevant_context (str): The distilled or filtered context containing only information relevant to the question.

"""

question: str

context: str

relevant_context: strThis class can now be used in our retrieval workflow graphs that we are going to plot, so let’s create that high-level function first.

def build_retrieval_workflow(node_name, retrieve_fn):

graph = StateGraph(QualitativeRetrievalGraphState)

graph.add_node(node_name, retrieve_fn)

graph.add_node("keep_only_relevant_content", keep_only_relevant_content)

graph.set_entry_point(node_name)

graph.add_edge(node_name, "keep_only_relevant_content")

graph.add_conditional_edges(

"keep_only_relevant_content",

is_distilled_content_grounded_on_content,

{

"grounded on the original context": END,

"not grounded on the original context": "keep_only_relevant_content",

},

)

app = graph.compile()

display(Image(app.get_graph().draw_mermaid_png(draw_method=MermaidDrawMethod.API)))

return graphWe can simplt call this function based on our three tyes of retrieval, let do that and see how each graph looks like.

# Create workflows

build_retrieval_workflow("retrieve_chunks_context_per_question", retrieve_chunks_context_per_question)

build_retrieval_workflow("retrieve_summaries_context_per_question", retrieve_summaries_context_per_question)

build_retrieval_workflow("retrieve_book_quotes_context_per_question", retrieve_book_quotes_context_per_question)We can further test the retrieval function we just created, but it’s better to test it later when we run our sub-graph RAG pipeline on complex queries.

We also need to create a sub-graph that will reduce hallucination in the answers, which is very important. For that, we first need to have a separate function to validate whether the answer is grounded in facts or not — we can code that.

def is_answer_grounded_on_context(state):

"""

Determines if the answer to the question is grounded in the facts.

Args:

state: A dictionary containing the context and answer.

Returns:

"hallucination" if the answer is not grounded in the context,

"grounded on context" if the answer is grounded in the context.

"""

print("Checking if the answer is grounded in the facts...")

context = state["context"]

answer = state["answer"]

# Use the is_grounded_on_facts_chain to check if the answer is grounded in the context

result = is_grounded_on_facts_chain.invoke({"context": context, "answer": answer})

grounded_on_facts = result.grounded_on_facts

if not grounded_on_facts:

print("The answer is hallucination.")

return "hallucination"

else:

print("The answer is grounded in the facts.")

return "grounded on context"The logic behind this function is the same as the way we are checking things before creating the sub-graph, LLM will be responding whether it is hallucinated or not.

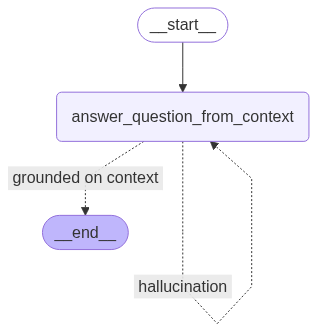

We need to code one last sub-graph that will help answer the query based on the context without creating hallucinations. Let’s plot that graph.

# Define graph state

class QualitativeAnswerGraphState(TypedDict):

question: str; context: str; answer: str

# Build graph

wf = StateGraph(QualitativeAnswerGraphState)

wf.add_node("answer", answer_question_from_context)

wf.set_entry_point("answer")

wf.add_conditional_edges("answer", is_answer_grounded_on_context, {

"hallucination": "answer",

"grounded on context": END

})

# Compile and show graph

display(Image(wf.compile().get_graph().draw_mermaid_png(draw_method=MermaidDrawMethod.API)))Let’s test the hallucinated pipeline before we move forward. Let’s forcefully induce hallucination and see if the LLM fails.

question = "who is harry?" # The question to answer

context = "Harry Potter is a cat." # The context to answer the question from

init_state = {"question": question, "context": context} # The initial state

for output in qualitative_answer_workflow_app.stream(init_state):

for _, value in output.items():

pass # Node

# ... (your existing code)

pprint("--------------------")

print(f'answer: {value["answer"]}')

#### OUTPUT ####

Answering the question from the retrieved context...

answer before checking hallucination: Harry Potter is a cat.

Checking if the answer is grounded in the facts...

The answer is grounded in the facts.

--------------------

answer: Harry Potter is a cat.So we limited the context to test if the LLM is going to hallucinate, and it does not, as it is answering based on the context only which is a good sign.

So now that we have coded the core components of our RAG pipeline, the most important part still remains to be done, the logic of our RAG pipeline. We first need to initiate a class object, which will then be further developed based on the logic we will be coding in our planner.

class PlanExecute(TypedDict):

curr_state: str

question: str

anonymized_question: str

query_to_retrieve_or_answer: str

plan: List[str]

past_steps: List[str]

mapping: dict

curr_context: str

aggregated_context: str

tool: str

response: strNext, we need to define how the plan will be executed, which means that our RAG is based on many components.

The logic here refers to how the plan will be carried out to solve complex queries that require rethinking. For that, the LLM can once again come in handy in this case too.

# Define a Pydantic model for the plan structure

class Plan(BaseModel):

"""Plan to follow in future"""

steps: List[str] = Field(

description="different steps to follow, should be in sorted order"

)

# Prompt template for generating a step-by-step plan for a given question

planner_prompt =""" For the given query {question}, come up with a simple step by step plan of how to figure out the answer.

This plan should involve individual tasks, that if executed correctly will yield the correct answer. Do not add any superfluous steps.

The result of the final step should be the final answer. Make sure that each step has all the information needed - do not skip steps.

"""

# Create a PromptTemplate instance for the planner

planner_prompt = PromptTemplate(

template=planner_prompt,

input_variables=["question"],

)

# Initialize the LLM for planning

planner_llm = ChatTogether(

temperature=0,

model_name="meta-llama/Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo-Free",

api_key=together_api_key,

max_tokens=2000

)

# Compose the planner chain: prompt -> LLM -> structured output (Plan)

planner = planner_prompt | planner_llm.with_structured_output(Plan)The most important part here is the prompt template. Based on the user query, the LLM will determine the individual tasks that need to be performed within our RAG pipeline. The final step should be generating the final answer. Since we are relying on the LLM, we are also stating in the prompt template not to skip steps.

We have three types of retriever information: summaries, quotes, and chunked. We need to define a plan for this in a refined format that can be executed accordingly based on the user query. So, let’s define that plan.

# Prompt template for refining a plan so that each step can be executed by a retrieval or answer operation

break_down_plan_prompt_template = """You receive a plan {plan} which contains a series of steps to follow in order to answer a query.

you need to go through the plan refine it according to this:

1. every step has to be able to be executed by either:

i. retrieving relevant information from a vector store of book chunks

ii. retrieving relevant information from a vector store of chapter summaries

iii. retrieving relevant information from a vector store of book quotes

iv. answering a question from a given context.

2. every step should contain all the information needed to execute it.

output the refined plan

"""

# Create a PromptTemplate instance for the breakdown/refinement process

break_down_plan_prompt = PromptTemplate(

template=break_down_plan_prompt_template,

input_variables=["plan"],

)

# Initialize the LLM for breaking down/refining the plan

break_down_plan_llm = ChatTogether(

temperature=0,

model_name="meta-llama/Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo-Free",

api_key=together_api_key,

max_tokens=2000

)

# Compose the chain: prompt -> LLM -> structured output (Plan)

break_down_plan_chain = break_down_plan_prompt | break_down_plan_llm.with_structured_output(Plan)In our prompt template, we are providing new knowledge to the LLM about our retriever database, along with some extra information, so that it can break down the plan accordingly.

Let’s test this plan executor we just coded and see how it takes steps to address our user query.

question = {"question": "how did the main character beat the villain?"} # The question to answer

my_plan = planner.invoke(question) # Generate a plan to answer the question

print(my_plan)

refined_plan = break_down_plan_chain.invoke(my_plan.steps) # Refine the plan

print(refined_plan)

#### OUTPUT ####

steps = [

'Identify the hero and villain using data from a vector store.',

'Find the climax or final clash using data from a vector store.',

'Analyze the hero’s actions in this clash using data from a vector store.',

'Determine the key action/strategy that defeated the villain using data from a vector store.',

'Summarize how the hero beat the villain using the retrieved context.'

]So it outputs a step-by-step chain-of-thought (CoT) approach based on our test question. It returns the steps as a list, where the final step is to provide the final answer. This shows that our plan executor is working correctly.

We also need to code the logic where the plan gets updated based on the past steps, the current plan, and the aggregated information. So, let’s implement that as well.

# Prompt template for replanning/updating the plan based on progress and context

replanner_prompt_template = """

For the given objective, come up with a simple step by step plan of how to figure out the answer.

This plan should involve individual tasks, that if executed correctly will yield the correct answer.

Do not add any superfluous steps. The result of the final step should be the final answer.

Make sure that each step has all the information needed - do not skip steps.

Assume that the answer was not found yet and you need to update the plan accordingly, so the plan should never be empty.

Your objective was this:

{question}

Your original plan was this:

{plan}

You have currently done the following steps:

{past_steps}

You already have the following context:

{aggregated_context}

Update your plan accordingly. If further steps are needed, fill out the plan with only those steps.

Do not return previously done steps as part of the plan.

The format is JSON, so escape quotes and new lines.

{format_instructions}

"""This prompt template serves to understand the step-by-step progress throughout our RAG pipeline, which has just enhanced our pipeline because it can now track and comprehend each step live while it’s active.

Let’s move on to the next step, which is to create a re-planner on top of this prompt.

# Define a Pydantic model for the possible results of the action (replanning)

class ActPossibleResults(BaseModel):

"""Possible results of the action."""

plan: Plan = Field(description="Plan to follow in future.")

explanation: str = Field(description="Explanation of the action.")

# Create a JSON output parser for the ActPossibleResults model

act_possible_results_parser = JsonOutputParser(pydantic_object=ActPossibleResults)

# Create a PromptTemplate for replanning, using the replanner_prompt_template defined earlier

replanner_prompt = PromptTemplate(

template=replanner_prompt_template,

input_variables=["question", "plan", "past_steps", "aggregated_context"],

partial_variables={"format_instructions": act_possible_results_parser.get_format_instructions()},

)

# Initialize the LLM for replanning

replanner_llm = ChatTogether(temperature=0, model_name="LLaMA-3.3-70B-Turbo-Free", max_tokens=2000)

# Compose the replanner chain: prompt -> LLM -> structured output (ActPossibleResults)

replanner = replanner_prompt | replanner_llm | act_possible_results_parserGreat! Now that we have coded the complete plan execution logic, we can move forward with creating the task handler logic.

Though we have completed the coding for plan execution, we also need a separate task handler that will decide when to use which sub-graph for each of the tasks.

The approach will be the same: we’ll start by creating a prompt template, and then build a chain on top of that template.

# Prompt template for the task handler, which decides which tool to use for a given task in the plan.

tasks_handler_prompt_template = """

You are a task handler that receives a task: {curr_task} and must decide which tool to use to execute the task.

You have the following tools at your disposal:

Tool A: Retrieves relevant information from a vector store of book chunks based on a given query.

- Use Tool A when the current task should search for information in the book chunks.

Tool B: Retrieves relevant information from a vector store of chapter summaries based on a given query.

- Use Tool B when the current task should search for information in the chapter summaries.

Tool C: Retrieves relevant information from a vector store of quotes from the book based on a given query.

- Use Tool C when the current task should search for information in the book quotes.

Tool D: Answers a question from a given context.

- Use Tool D ONLY when the current task can be answered by the aggregated context: {aggregated_context}

Additional context for decision making:

- You also receive the last tool used: {last_tool}

- If {last_tool} was retrieve_chunks, avoid using Tool A again; prefer other tools.

- You also have the past steps: {past_steps} to help understand the context of the task.

- You also have the initial user's question: {question} for additional context.

Instructions for output:

- If you decide to use Tools A, B, or C, output the query to be used for the tool and specify the relevant tool.

- If you decide to use Tool D, output the question to be used for the tool, the context, and specify that the tool to be used is Tool D.

"""We are defining four tools, each one corresponds to a separate sub-graph for each of the retrievers, so they can be called as needed. This is exactly what each tool represents in our prompt template. The last tool is for generating the final answer.

Now, let’s create a chain on top of it.

# Define a Pydantic model for the output of the task handler

class TaskHandlerOutput(BaseModel):

"""Output schema for the task handler."""

query: str = Field(description="The query to be either retrieved from the vector store, or the question that should be answered from context.")

curr_context: str = Field(description="The context to be based on in order to answer the query.")

tool: str = Field(description="The tool to be used should be either retrieve_chunks, retrieve_summaries, retrieve_quotes, or answer_from_context.")

# Create a PromptTemplate for the task handler, using the tasks_handler_prompt_template defined earlier

task_handler_prompt = PromptTemplate(

template=tasks_handler_prompt_template,

input_variables=["curr_task", "aggregated_context", "last_tool", "past_steps", "question"],

)

# Initialize the LLM for the task handler

task_handler_llm = ChatTogether(temperature=0, model_name="meta-llama/Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo-Free", api_key=together_api_key, max_tokens=2000)

# Compose the task handler chain: prompt -> LLM -> structured output (TaskHandlerOutput)

task_handler_chain = task_handler_prompt | task_handler_llm.with_structured_output(TaskHandlerOutput)So far, we have coded the sub-graphs, the plan executor, and the task handler to decide which sub-graph should be executed.

However, we still need an approach to generate the plan without biases/hallucinations. That’s exactly what we’re going to implement in the next step.

In order to generate a general plan without any biases based on prior knowledge of any LLM, we first anonymize the input question and map the named entities into variables.

# --- Anonymize ---

class AnonymizeQuestion(BaseModel):

anonymized_question: str

mapping: dict

explanation: str

anonymize_question_chain = (

PromptTemplate(

input_variables=["question"],

partial_variables={"format_instructions": JsonOutputParser(pydantic_object=AnonymizeQuestion).get_format_instructions()},

template="""You anonymize questions by replacing named entities with variables.

Examples:

- "Who is harry potter?" → "Who is X?", {{"X": "harry potter"}}

- "How did the bad guy play with Alex and Rony?" → "How did X play with Y and Z?", {{"X": "bad guy", "Y": "Alex", "Z": "Rony"}}

Input: {question}

{format_instructions}

""",

)

| ChatTogether(temperature=0, model_name="meta-llama/Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo-Free", api_key=together_api_key, max_tokens=2000)

| JsonOutputParser(pydantic_object=AnonymizeQuestion)

)After the plan is constructed based on the anonymized question, we de-anonymize the plan by replacing the mapped variables with the original named entities.

class DeAnonymizePlan(BaseModel):

plan: List

de_anonymize_plan_chain = (

PromptTemplate(

input_variables=["plan", "mapping"],

template="Replace variables in: {plan}, using: {mapping}. Output updated list as JSON."

)

| ChatTogether(temperature=0, model_name="meta-llama/Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct-Turbo-Free", api_key=together_api_key, max_tokens=2000) .with_structured_output(DeAnonymizePlan)

)Great! Now that we have defined all the major components of our newly sub-graph-dedicated pipeline, we just need to initialize it so that we can test it on our sample user queries.

We have coded all the components, now let’s compile each and every part of the RAG pipeline and begin evaluating it.

def execute_plan_and_print_steps(state):

# Set the current state label

state["curr_state"] = "task_handler"

# Get the current task and remove it from the plan

curr_task = state["plan"].pop(0)

# Prepare inputs for the task handler chain

inputs = {

"curr_task": curr_task,

"aggregated_context": state.get("aggregated_context", ""),

"last_tool": state.get("tool"),

"past_steps": state.get("past_steps", []),

"question": state["question"]

}

# Invoke the task handler to decide the next tool and query

output = task_handler_chain.invoke(inputs)

# Track completed task

state["past_steps"].append(curr_task)

# Save query and selected tool

state["query_to_retrieve_or_answer"] = output.query

state["tool"] = output.tool if output.tool != "answer_from_context" else "answer"

# If answering from context, store the specific context

if output.tool == "answer_from_context":

state["curr_context"] = output.curr_context

return stateNow we can visualize this sub graph RAG approach, showing the code of visualizing the pipeline will be veyrdifficult to understand but it’s vailable in the repo. Let’s see the visualization.

Now if we understand a high level overview of our finalized RAG pipeline …

- We start by anonymizing the question

- Next, a planner creates a high-level strategy

- Then, the plan is de-anonymized to reintroduce context

- The plan is broken down into smaller tasks

- Each task is handled by selecting an appropriate tool

- If the tool is to retrieve quotes, chunks, or summaries, data is fetched

- After retrieval, the system may replan based on new info

- If the question can be answered, the final answer is generated

- The process ends

So, this is a very high level overview of what we have coded so far.

We want to test our finalized pipeline with three different examples. The first example is designed to make the model fail intentionally, so we can observe how the pipeline handles a question whose context simply doesn’t exist.

# -----------------------------------------------------------

# Example: Run the Plan-and-Execute Agent for a Sample Question

# -----------------------------------------------------------

# Define the input question for the agent

input = {

"question": "what did professor lupin teach?"

}

# Execute the plan-and-execute workflow and print each step

final_answer, final_state = execute_plan_and_print_steps(input)

#### OUTPUT ####

...

...

the final answer is: The answer was not found in the data.The output of this example is very long because the agent repeatedly tries and fails to find the information.

This is actually a good sign, as it demonstrates that the system does not invent (or “hallucinate”) an answer when the information is not present in its knowledge base.

Now, let’s move on to an original example test where we actually want an answer, because the context does contain relevant information, so let’s do that.

# -----------------------------------------------------------

# Example: Run the Plan-and-Execute Agent for a Complex Question

# -----------------------------------------------------------

# Define the input question for the agent.

# This question requires reasoning about the professor who helped the villain and what class they teach.

input = {

"question": "what is the class that the proffessor who helped the villain is teaching?"

}

# Execute the plan-and-execute workflow and print each step.

# The function will print the reasoning process and the final answer.

final_answer, final_state = execute_plan_and_print_steps(input)

#### OUTPUT ####

...

...

the final answer is: The professor who helped the villain is

Professor Quirrell, who teaches Defense Against the Dark Arts.I have truncated the output here to avoid confusion, but the final response validates the logical reasoning of our RAG pipeline confirming that it works correctly when the context contains information relevant to the query.

This output demonstrates the agent’s ability to break down a complex query into simpler, solvable parts and chain them together effectively.

Now comes the final step: we need to test the chain-of-thought (CoT) reasoning capability of our pipeline, so let’s do that.

# -----------------------------------------------------------

# Example: Run the Plan-and-Execute Agent for a Reasoning Question

# -----------------------------------------------------------

# Define the input question for the agent.

# This question requires reasoning about how Harry defeated Quirrell.

input = {

"question": "how did harry beat quirrell?"

}

# Execute the plan-and-execute workflow and print each step.

# The function will print the reasoning process and the final answer.

final_answer, final_state = execute_plan_and_print_steps(input)

#### OUTPUT ####

nswering the question from the retrieved context...

answer before checking hallucination: Reasoning Chain:

The context states that when Harry touched Quir ... and burned.

The context explains this is due to a powe ... ove.

Therefore, Harry defeated Quirrell not with a spell ... possessed by Voldemort.

Final Answer: Harry defeated Quirrell because his mother ... to burn upon contact.This example shows that the system can do more than just extract facts, it can follow a structured reasoning process to build a comprehensive explanation for “how” and “why” questions.